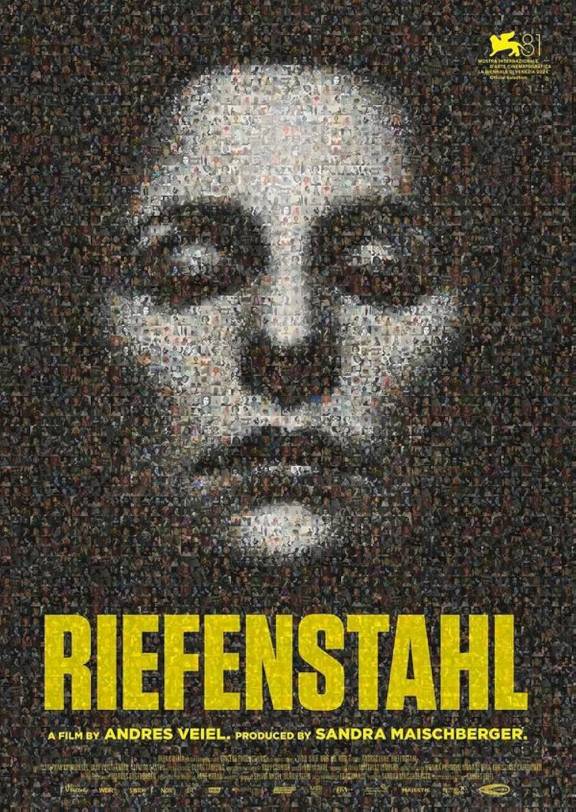

Riefenstahl

Leni Riefenstahl (1902-2003) is zeker voor een hedendaags publiek veruit de bekendste regisseur die in opdracht van de nazi’s werkte. Haar voortdurende roem dankt ze aan de filmische bravoure van innovatieve, nog altijd invloedrijke propagandadocumentaires als Triumph des Willens (over de partijdag in Neurenberg, 1934) en Olympia (over de Spelen van Berlijn, 1936).

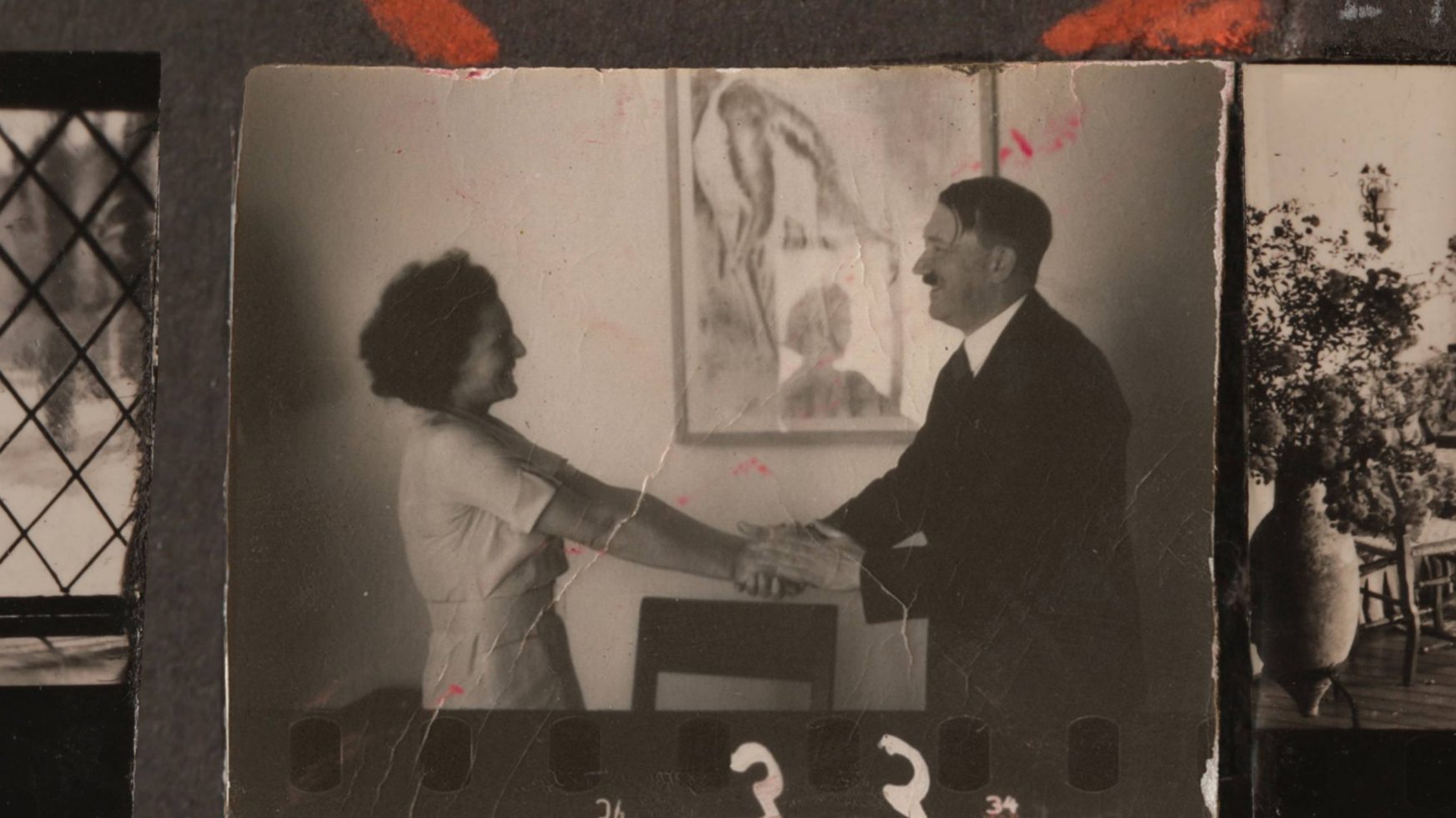

Wellicht net zo berucht is de vasthoudendheid waarmee ze haar historische onschuld claimde – en die van haar esthetiek. Ja, zij was onder de indruk van Hitler, maar had slechts een kans gegrepen om haar talenten te gebruiken.

Andres Veiel, eminent chroniqueur van de recente Duitse geschiedenis, had voor zijn fascinerende portret voor het eerst toegang tot een schat aan privémateriaal uit de nalatenschap van Riefenstahl en haar veertig jaar jongere partner Horst Kettner. Milder werd hij er niet van. Meer dan in eerdere films over haar wordt duidelijk hoezeer Riefenstahl – zich wentelend in zelfingenomen slachtofferschap – in een gunstig licht gezien wilde worden. Bovenal toont Veiel dat Riefenstahl niet onwetend kan zijn geweest van het wrede lot van medewerkers en figuranten.

- 19:00

Kies tijdstip

- Film

Leni Riefenstahl (1902-2003) is zeker voor een hedendaags publiek veruit de bekendste regisseur die in opdracht van de nazi’s werkte. Haar voortdurende roem dankt ze aan de filmische bravoure van innovatieve, nog altijd invloedrijke propagandadocumentaires als Triumph des Willens (over de partijdag in Neurenberg, 1934) en Olympia (over de Spelen van Berlijn, 1936).

Wellicht net zo berucht is de vasthoudendheid waarmee ze haar historische onschuld claimde – en die van haar esthetiek. Ja, zij was onder de indruk van Hitler, maar had slechts een kans gegrepen om haar talenten te gebruiken.

Andres Veiel, eminent chroniqueur van de recente Duitse geschiedenis, had voor zijn fascinerende portret voor het eerst toegang tot een schat aan privémateriaal uit de nalatenschap van Riefenstahl en haar veertig jaar jongere partner Horst Kettner. Milder werd hij er niet van. Meer dan in eerdere films over haar wordt duidelijk hoezeer Riefenstahl – zich wentelend in zelfingenomen slachtofferschap – in een gunstig licht gezien wilde worden. Bovenal toont Veiel dat Riefenstahl niet onwetend kan zijn geweest van het wrede lot van medewerkers en figuranten.